Sixty Years a Mime Artist – Is that even possible?

This interview with Milan Sládek was conducted by Frank Meyer, long-time dramatist and actor with the Kefka Theatre in Cologne.

1955: In socialist Czechoslovakia, an unknown, 17-year-old mime artist gives his first, self-taught solo performance.

2015: That same artist, now internationally acclaimed, premieres his rendition of Sophocles’ Antigone, a compact work of art combining elements of movement, mask-play, narrative, and music.

As a young, debuting mime artist, could you imagine that you would still be working at seventy-seven years old? Most young people think they'll never live to be that age, but still, did you have any idea that you would be around for this long?

To be honest, I really didn't. I never seriously thought about it because I have felt old since I was eighteen (laughter). And that's the way it has stayed. My age has never been of much concern to me. Only to others.

Okay, allow me to rephrase that: Thinking back, can you understand the motivations of your 17-year-old self?

Yes, I think I can understand his motivations. I can appreciate his passion, his uncertainty when trying new things - that's stuck with me until this day. I also understand his propensity to take risks. Because honestly, how many people would ever so much as consider doing some of the things that I've done? Maybe that's why I became a mime artist in the first place, and why I later moved abroad. There are bound to be some people who have done that, but not too many. But to found the Kefka Theatre as the only mime theatre, not just in Cologne, but in the whole of Western Europe, that's something most people would consider utterly foolish! No-one has attempted anything like it since.

Back in 1955, though, you couldn't have imagined that you would ever get that far. At that time, you were in Bratislava, giving your first shows. Let's fast forward through your career: in 1958, you joined your first company in Bratislava. In 1959, you and Eduard Žlábek established your own company and worked at the famous E. F. Burian – D34 Theatre in Prague. On March 11, 1960, you created your signature character, Kefka. You then returned to Bratislava and, in 1962, you joined the mime company at the Slovak National Theatre. In 1963, you started touring abroad. In 1965, you toured across Germany, reaping many awards along the way. In 1968, the Prague Spring broke out, and then, in winter, everything ground to a halt. The theatre was closed down, with the core of the company staying abroad. In 1970, you relocated to Cologne. In 1974, you founded the Kefka Theatre. Six years later, you organised the first international mime festival, the Gaukler, in the city of Cologne. On New Year's Day in 1987, the Kefka Theatre staged its last performance, and the last (13th) edition of the Gaukler Festival took place in 1990. The Berlin Wall had collapsed. The wind of change was blowing in the air.

That's right. In the beginning of the 1990s, I got a call from František Mikloško, who was then Speaker of the Slovak National Council, and he asked, 'How would you like to start a mime theatre in Slovakia?'

I assume you had to think on that, right?

Of course, I thought on it for about 20 or 30 seconds. Then I accepted. I chose to revive the abandoned premises of the old Arena Theatre. At that time, the building belonged to Slovak Television and was being used to store props. The Arena had been closed since the 1930s. During the Second World War, it had served as a detention camp for prisoners who were later shipped off to concentration camps. It was built around the year 1900 at the former venue of the Bratislava Amphitheatre, where the world-class director Max Reinhardt had begun his incredible acting career. By the way, his father came from Lamač, a village near Bratislava.

So despite the difficult conditions at the time, you managed to save the historic venue?

That's right. The next 10 years, which I spent in Bratislava, were very productive for me. The restoration of the theatre was financially supported not only by the state, but also by our viewers, who would chip in to help us buy the construction materials. One fan of mine from Cologne, who owned glass factories in Aachen and Nitra, sponsored the glazing works, which must've been worth around 28 thousand Deutschmarks. He just said, 'I wanted to help that young man from Cologne.'

Can you compare the various times in your life: Bratislava and Prague between 1955 and 1968, Cologne between 1974 and 1987, and then Bratislava until 2002? Which of those periods was the most interesting for you as an artist, and which one did you find most challenging in terms of the economic and political circumstances?

These questions all blend into one. Prior to August 1968, our company in Bratislava was doing rather well, especially in comparison to the other theatres. We received state funding. Socialism at that time was trying to present its “human” face, and supporting art was a very important aspect of that strategy. I only started to have problems after I was approached by the Secret Police – they wanted to sign me. Since at least 1963, I had been touring in the West, but also in the East, and even in India. I naturally refused. I didn't want to go down the road that many actors did. They were routinely informing on their fellow artists, even on me. I was told that by an employee of the Czechoslovak Embassy in Bonn. I couldn't betray my conscience.

That's a very admirable position. As far as I know, you never betrayed your conscience, not even when you were approached by Western intelligence, when you were already living in Germany. When you came to Cologne, did you mingle with the other Czech and Slovak exiles? If not, why?

It's interesting how well Western intelligence worked. In late 1969, I was invited to Switzerland along with another 150 immigrants from the whole of the Eastern Bloc. We had been invited by an American organisation which had covered all the costs, including the travel and accommodation costs. It was very strange. Even today, when I think back to it, I feel somewhat ill-at-ease. How did they even know how to find us? They wanted us to criticise the socialist establishment; we were supposed to recount our negative experiences with the regime. The whole discussion was being recorded. To this day, I don't know if they broadcast it or just tossed it in the archives.

Many of your compatriots lived in Cologne, yet there were no institutions which could have covered the costs?

No, but there were many people who were politically engaged! In 1970, I relocated from Sweden to Cologne and I met people whom I had known from back in Switzerland – the founders of the INDEX Publishing House, which specialised in promoting Czech and Slovak exile literature. Most of the texts had been smuggled out of Czechoslovakia or written by immigrants living abroad. All these people were very helpful and kind. Slovak immigrants didn't really feel the urge to fraternise as much as the Czechs. Even I – given that I had been forced to join socialist organisations such as the Pioneer Movement and the Association of Socialist Youth – was reluctant to join any kind of organisation.

Politics plays a major role in theatre, albeit not a direct one. Indeed, the indirect of influencing the arts are often much more efficient. What's important is how the audience view the story unfolding on stage and what they can take from it, in terms of both their private and public lives. Would you say that pre-1968 era, an era of dictatorship and censorship, but also of conflict, was politically and artistically more rewarding than the democratic era, where you can do almost anything in theatre apart from smoking, but at the same time, it appears as though nothing is really that important?

Back then, we in Czechoslovakia were convinced that it was very important to criticise the establishment. We would do it in indirect ways, through our work. It was also quite effective – especially because we thought that we shared the opinions of the audience. Even the “responsible” choice of staging decidedly non-political shows would appear like a protest or an insult to the official tendencies and themes, given the ideology of the socialist regime.

In the West, you did not face the same problems.

No, I didn't. I found myself in the West and suddenly I could say whatever I wanted, whatever I thought was important. I could complain and criticise; I could even do all that with a cigarette dangling off the corner of my mouth. There was no censorship, but at the same time, self-censorship failed me. You have nothing to fall back on. The 1968 movement and its impact on Western society, that was all very exciting. Everything was buzzing, positive, rebellious, we saw new perspectives; new worlds were opening up to us. How were we supposed to take all that on stage without appearing histrionic? We had to find our own ways.

Throughout its long history, which goes back thousands of years, mime has had both high and low points. There have been times when the art form flourished, but also times when it almost completely disappeared. The seventies and eighties especially were a time when mime flourished, partially thanks to you. What happened that changed that?

Mime artists, illusionists, jugglers, street artists, we were all “made” in 1968. That's why that time is considered to be the renaissance of mime. The theme of rebirth, which was then slowly seeping into the wider public, was always a dominant theme in mime and the related art forms, along with other important themes such as antimilitarism, antiauthoritarianism in childrearing, women's emancipation, anti-nuclear, homosexual rights, the environment…

...and the rediscovery of sensuality, physicality, but also of theatre, which for so long had been focused solely on the spoken word of poets or the slogans of state ideologues.

Yes, the individual was again at the centre of our attention. This is an area where mime has always had a very strong voice, so to speak. Ever since the beginning, we received very good feedback from the audience who frequented our small theatre, and later, en masse, the Gaukler Festival. We routinely had 30,000 people attending the ten-day festival. We experienced this phenomenon not only in Cologne, but also in other German cities, and elsewhere in the world. Over several decades of working with the Goethe Institut, I saw mime enjoy great popularity. Our shows were always sold out, even when we were playing in large theatres for 2000 or more people. We performed on each continent. It was truly a marvellous time.

But it's not that way anymore.

No, because these days people want consumer products, whether it's television, music, or gastronomy. Audiences today are completely different to the audiences of 25 years ago. The viewer is often surprised when a mime show ends and he experiences it as a new – or rediscovered – art form.

Does that affect your work?

Not in any significant way, but I do view it as proof of the fact that mime in theatre is something special and important. And I'm not done yet!

Are there signs which suggest that mime might experience another boom in the coming years? Or is it already happening? The Schauspeilhaus in Cologne now offers puppet and mask theatre as new art forms.

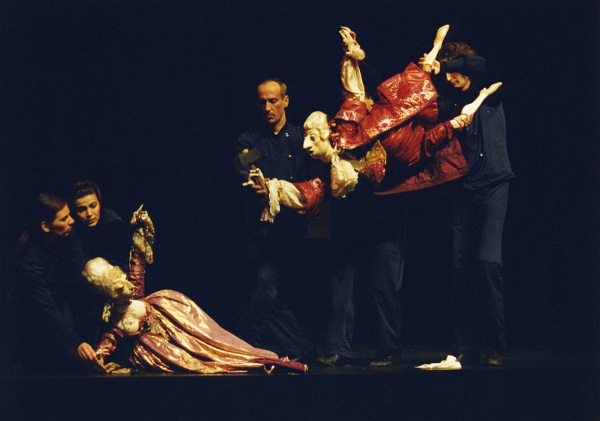

I experienced that myself in Cologne. My puppets for The Marriage of Figaro found talented reenactors. That's great! I, too, was inspired by the great Japanese puppet theatre Bunraku. Who could resist? Not even Bertolt Brecht and the other European thespians. And that's why we can see today plays where the actors move a lot. I, however, think that moving and using your whole body to communicate something are two different things. It has to do with preparation and attitude. In any case, it's good that these art forms have found their audience in Germany. In other countries, like Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Russia, they have always been considered equal to the other, more conventional ones.

Do you think that mime is on the ascent as a separate theatre genre, not just as a style element?

I'm completely confident that mime has a bright future. Everything points to that effect. We can draw some comparisons between now and the 1970s and 80s. It's difficult to tell what form it will take. Today, we lack visionaries like Volker Aurich in Cologne or Hans-Jürgen Nagel in Bonn, who, thanks to their enthusiasm sensed the renaissance of this art form and tried to support it within the limits of their abilities. In 1975, all I had to do was ask whether the Sparkassen Foundation would support a mime festival – and Mr. Aurich immediately got involved! Today, many people do non-verbal theatre. They are embarrassed when people call them mime artists. Most people, when they hear mime, immediately think of the imaginary wall – by the way, who's responsible for that? So if someone like me appears, who can find the right people to work with, like you, then we can certainly expect a renaissance of mime as a standalone genre.

(smirk) Thank you! Considering the reduction of mime, or rather, of its image, to technique (such as the imaginary wall or walking in place), you find yourself asking, who is responsible? You must have some idea. You have taught this art form in your theatre, later at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen, and you have also given courses all over the world.

Mime, for me, is a pure form of performance art. That's how I personally conceived my pedagogical work. The important question is, what do we understand by the term mime technique? Is it just the grasp of a certain skillset that has already been developed and promulgated? Is it not more important to harness your emotions and channel them into authentic expression? Unfortunately, as I have found out in many mime schools, what most people understand as technique is the adoption of certain stylised depictions of reality, which were thought up and established as mime technique. In other art forms, something like that wouldn't pass. Is imitating another artist the first step towards developing a performer's creativity? I don't think so. To me, it seems like a dead end, which only the greatest of artists can overcome.

The most radical mime artist of all was Etienne Decroux, teacher of Jean-Louis Barrault and Marcel Marceau, who, in the 1920s and 30s, devised the mime corporel method – the sort of basic grammar for any mime artist. When Barrault decided to go his own way, he made his former teacher very angry.

Etienne Decroux undoubtedly made a great contribution to the development of modern mime. His first works were notably influenced by other contemporary art forms. Back in 1980, the Gaukler Festival…

…was dedicated to Decroux!

Yes! We showed various clips and staged a few reconstructions of his works, which he had made in the 1960s with his students in New York City.

Such as The Trees, Passage of Man across the Earth, and The Factory.

Exactly. I was fascinated by those works. You can tell how much of an impact the visual arts styles of the time, and especially cubism, had on Decroux. But what has remained somewhat foreign and unacceptable to me are his training routines which were designed to facilitate complete immersion in mime corporel. He asked his students to mimic them. I don't think that's a good pedagogical approach. It's ideological, even religious – and I'd had enough of that during the socialist era.

What about Marceau?

In my view, Marcel Marceau was the only one to free himself from the shackles of Decroux's method owing to his talent, intelligence, and strength of character. Watching clips of his earlier shows, I'm always absolutely taken by his ability to recount themes and stories. He was excellent at working with forms, rhythm, and composition. With Marceau, there are many questions regarding his technique and approach to teaching. Jacques Lecoq, who is known as one of the founders of the French Mime School, emphasised the clown element in pedagogy. What I miss in the three pillars of the French Mime School is the inner dimension of expression, which is the main pillar of acting – developing your own personal technique.

You didn't have French teachers. According to Ladislava Petišková, you had to – and fortunately, were able to – draw on other sources.

I know that when I speak critically about the three fathers of the art of mime, some people might take to considering me as a niggling Eastern-European. But both in the East and in the West, we ask the same important questions:

HOW DO I VIEW REALITY?

HOW CAN I FIND A WAY TO MYSELF?

HOW DO I LEARN TO UNDERSTAND THE WORLD AND THE PEOPLE AROUND ME?

HOW CAN I DEVELOP MY OWN FORM OF EXPRESSION FROM MY NEEDS AND ABILITIES?

Well, certainly not by being a member of some near-ideological cult.

That wouldn't have worked at a theatre devoted exclusively to mime, such as the Kefka Theatre in Cologne, which had its own company and daily programme. A theatre like that must always strive to offer its regular audience something new and different.

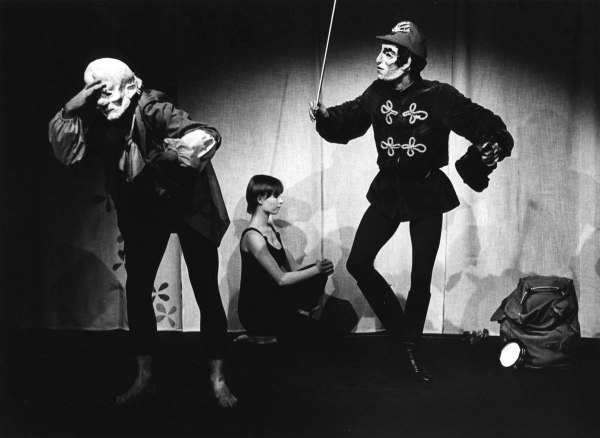

Exactly, and that's what we always tried to do. With every new production – remember the comic mime Ubu, based on the scandalous work by Alfred Jarry – we would question the visual tradition and challenge the expectations of at least a part of the audience until they finally accepted something new and unusual. That's how we gradually earned the trust of our viewers.

The theatre was open for thirteen years. What historical importance would you ascribe to the Kefka Theatre in Cologne – seeing as it was the only theatre devoted solely to the art of mime?

First of all, it confirmed my conviction that mime is equally valuable as the other theatre forms, and that it can build up a large audience. Initially, many of my friends and acquaintances thought that my ambition to found a mime theatre amounted to lunacy. They said that Cologners were only interested in the carnival and the opera. At best, they said, the people would come see a guest performance by Marcel Marceau. And it wasn't easy. For a long time, we only had one technician, who filled all the roles – he was a set technician, a sound technician, as well as a driver – it was Pierre Hoffman.

Even the mime artists had other duties apart from training and performing. They had to do the dramaturgy, help with the props and the masks, hand out leaflets and posters and send out the programmes via post.

That was the way it was. But given our conditions, we did very well. We managed to make a name for ourselves outside the city, both with the audience and with the media. That only further cemented our conviction that you had to be a little crazy and believe in the power of mime, that it could speak to all people regardless of age or social background. We even got a boost from the scientific community, which, in those days, took a great interest in body language and later, in mirror neurons.

These days, you see quite a few seminars on body language for managers and politicians because a lot of them believe that they'll become more successful negotiators if they learn to use their body language. But I doubt that that will help bring back mime as an art form.

Honestly, so do I. But there are many great performers, both individuals and groups, who can facilitate the renaissance of mime, much like there were in the 1970s. Why are they only known to a small group of the initiated and not the wider public, you ask? You were there when the Kefka Theatre was born, so you know how long it took for us to build up an audience, and how we were always trying to surprise and dazzle the viewers. Our efforts were finally rewarded, and we managed to establish one of the most successful and famous mime festivals in the world, which undoubtedly served as inspiration to many young mime artists. The festival had an international audience. Cologne had become the 'Mecca of Mime', as they often wrote in the newspapers. And the audience never thought that that was somehow unusual. We had managed to establish this specific art form and etch out a place for it among the more conventional theatre forms. Comparing ourselves to the other theatres, which often received funding from the city or the state, we had far fewer resources at our disposal. One day, the city manager Kurt Rossa – a great fan of the Kefka Theatre – told me, 'Unfortunately, we couldn't find anyone who would convince the citizens of Cologne of the lasting value of your project'. But let's leave that alone. I was grateful to everyone who helped keep our theatre going. I think that we really paid it all back in full. We performed in 55 countries, at innumerable festivals; I spent 25 years working with the Franco-German Youth Office.

Let us return to Antigone. What made you want to stage this work – beside the fact that it's an ancient drama, and the antiquity was a time when mime art flourished? Did you draw on the present? Not long ago, there was a Roma family in France and the authorities didn't allow them to bury their child at the city cemetery.

I didn't know that. That's outrageous! Can anyone imagine what the family must have gone through? It's really an indictment of our species that so little has changed in 2500 years. That's how old the play is, and look, it's still so relevant! The ancient satirist Lucian writes in the book On Dance that Roman mime artists used to stage mythological musicals. They also performed Greek tragedies. When I was reading the book in the 1960s, my imagination was awhirl with ideas. I could picture what it would be like if I were to ever stage Antigone. At that time, a new translation of the drama was made by Slovak poet Ľubomír Feldek. And now, decades later, the spontaneous idea finally found its way from my head to the stage.

These days we call that “slowing down”

You know, at Kefka, but even before, in Prague and Bratislava, we would regularly stage works which celebrated the times when mime was a popular art form. Thanks to newspaper articles and the brilliant biographical novel, The Greatest Pierrot by Czech writer František Kožík, I got to know a mime artist who has served as a great source of inspiration for me: Jean Gaspard Deburau. He was the most popular Pierrot, and in the first part of the 19th century, in his loose white costume, he captivated not only the regular guests of the Theatre des Funambules, but also many artists and intellectuals of that era. I have staged his Rag-and-Bone-Man as a way of honouring his legacy. Some time later, I brought Deburau to the stage of the Nová Scéna Theatre in Bratislava as co-author, director and protagonist of the musical Grand Pierrot. In the 18th century, many composers fell in love with new dance, classical ballet, but many of them, such as Christoph Willibald Gluck, also composed mime ballets. I found his Don Juan really exciting and staged it as well.

I remember – that was the most difficult role I have ever played.

How come? You played the Commander!

Exactly. It was cruel. After my character dies on stage, I come back as a ghost – grey and motionless. In Mozart, I would at least be able to sing.

Nice point! Mozart was indeed a lover of mime. His KV 446 was inspired by a fragment in Pantalon and Columbine, in which he was a Harlequin. I considered it a great honour that I could stage that piece at the 2006 Mozart Festival in Vienna. It was really successful.

And The Marriage of Figaro?

I staged that for the Slovak National Theatre Opera, together with Monteverdi's Coronation of Poppea. Oh, and I have done three projects with young German, French and Slovak students under the auspices of the Franco-German Youth Association. I also held a photo exhibition in the City Gallery and brought six of my own shows into the Arena with the new mime company… We did so much in Bratislava. And we achieved that even despite the difficult conditions in the newly-emergent country and the corruption and incompetence of the bureaucrats. But in 2002, I decided to return to Cologne, my former home.

You even brought the Gaukler Festival to Bratislava.

Yes, also to the Arena Theatre. The festival was renamed as “Kaukliar” and was held six times featuring performers from all over Europe, as well as from China, Japan, and Canada. It was a real magnet for audiences. I always took care that I presented the diversity and richness of mime like we used to do in Cologne. For me, it's important to show that mime is in fact so much more than just the imaginary wall. I want to show not only the current diversity of the discipline, but also to draw on its rich history and present the great impact of mime on theatre. And that's why I often work with ancient drama. As the inspiration for Jupiter and other works, I used some fragments from Ovid's Metamorphoses. The premiere was performed at the famous Dionysus mosaic in the Romano-Germanic Museum in Cologne. In Ancient Rome, mime was incredibly popular. The Romano-Germanic museum was established in the same year as the Kefka Theatre – 1974. When we had to close down in 1987, my colleagues and I stood before the Cologne House opposite the museum as artefacts. But it didn't help (laughter).

I remember. Did you conceive Antigone as a classical project?

To the contrary! I was extremely excited to be working with masks, texts and music just like they used to do in Ancient Rome, and to rehabilitate solo mime, which has slowly been disappearing from the stage. But the lamentable timelessness of Antigone and the fact that the actors and the audience are modern, 21st-century people, does not allow classicality.

Last question: What is your life's masterpiece?

(smirk) Am I that old already?

Well, you're not too old, but you're certainly the oldest working mime artist in the world.

Kazuo Ohno, the butho dancer, was 100 years old when he gave his last performance!

But he only started at 43…

And he started his international career when he was 72.

Alright then, let's not talk about that. What have you got planned for the upcoming 23 years?

I would rather keep that a secret.

FM & MS: The rest is silence. (They both laugh)

Postscript, Kefka Theatre in Cologne

Ladislava Petišková writes at length about my colleagues in Prague and Bratislava, so we cannot remain silent, and we have to mention at least some of the people with whom I worked at the Kefka Theatre in Cologne. Our beginnings were difficult because there were many people who were sceptical about our opening the theatre, including my long-time friend and fellow mime artist, Eduard Žlábek. He was there with me in the beginning as an artist, a trainer, a docent, and a director. The whole economic burden was on my shoulders. When I remember how I was recruiting the first members of the company…

At that time there weren't many people who took an in interest in mime. Almost desperate, I turned to famous mime schools, saying that I was looking for new members for an emerging company. Several young performers signed up, but it later turned out that they couldn't really hold their own in an exclusive mime theatre, which requires a large scale of expression. I was left with no other option but to “rear” my own performers at workshops and courses and later engage them as permanent or guest performers.

You, Frank, were very active both as an actor and a dramatist, and you contributed to the popularity of the theatre. You provided the theoretical framework of the Gaukler Festival, and as docent in the theory and history of mime at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen, you showed me a new way of training mime artists.

How did you find working with us in the company as director of the theatre and as a colleague on stage? I know you could probably talk about it for hours.

You should know that, as a mime artist, I tend to be rather reticent.

Yes, I just remembered.

In all honesty, I can say that without all those great people, I would never have made it. You all did theatre 24 hours a day. 25, even! You always gave it your all, not only in trainings, but also when building sets, touring, handing out tickets… Frank, whenever I think back to those wonderful times, I feel extreme gratitude. You were all like family to me, although there may have been some who saw it differently. And now my question for you: How did you find working with me – as a colleague and a boss? And please, be gracious!

Well, there was always a lot of work. It was rewarding and edifying, simple and difficult, and only rarely something in between. But it was never boring! It was great fun!

(smirk) Thank you!