Lukáš Timulák - My Path to Choreography

Kristián Kohút On January 21, 2016, as part of the Petite Mort triple bill (Radačovský, Timulák, Kylián), the Ballet Company of the National Theatre in Brno (NDB) performed the premiere of Masculine/Feminine, a ballet by Slovak choreographer Lukáš Timulák.

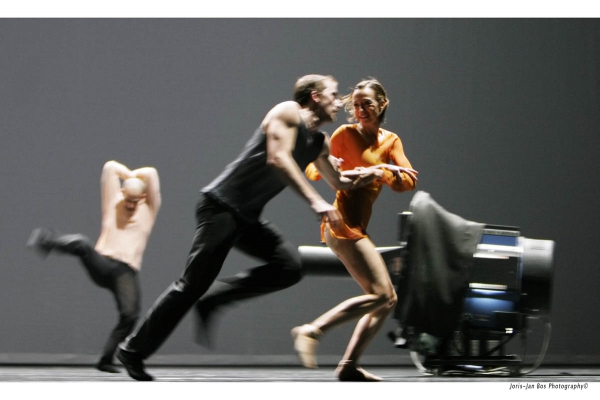

In Masculine/Feminine, Lukáš Timulák and Peter Biľak (texts, set and costume design) created a humorous dance miniature which explores the innate differences between the sexes. The work features eight performers in short choreographic vignettes which, in a candid but playful way, illustrate established stereotypes. On the stage, which is set up to look like a sitting room, the satirical vignettes join together with the narrative to produce a self-contained work of art. They at first appear unrelated, but they nonetheless flow one from the other. The choreographer was not afraid to combine powerful movements with more sensitive movement patterns, which are sometimes intended as caricatures of heightened emotional states. The quality of the performance is evidenced not only by the very positive response in the auditorium of the Janáček Theatre in Brno, but also by its subsequent stagings in the Netherlands (world premiere: February 24, 2011, NDT 2), Norway, and Austria.

Masculine/Feminine, Timulák's path to choreography, as well as his multidisciplinary projects and sources of inspiration are examined in greater depth in the following interview, which the author conducted himself.

Already as a student at the Eva Jaczova Dance Conservatory in Bratislava and later at the Academy of Classical Dance in Monte Carlo, you gravitated towards contemporary ballet, or rather, towards modern dance forms in general. At a time when your contemporaries were exploring the beauties of classical ballet, you were immersed in the work of Balanchine, and when they finally transitioned to Balanchine, you were already looking towards contemporary choreographers. Can you explain your dance development?

It's true that I've been inspired by alternative dance forms ever since I was a student, but I still very much appreciate classical dance, because it gives me a strong professional foundation. Over the course of time, I started to encounter certain sentiments that were more appropriate to contemporary dance. It all formed naturally and gradually. During my studies in Monte Carlo, new doors began to open for me; I got new opportunities and tried to make the most of them. I have always been driven by curiosity and a hunger for knowledge and information.

For three years, you performed with Les Ballets de Monte Carlo. Later, you spent ten years with the NDT, where you worked with many contemporary choreographers of international renown. Has the artistic practice fulfilled your expectations?

With Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, I danced choreographies by Balanchine, Maillot, Tharp, and Duato, and I began to explore new forms of dynamics, which I embraced and didn't want to give up. My transition into the NDT was really quite natural. While there, I started working with choreographers like Kylián, Forsythe, Ek, Naharin, Lightfoot/Leon, Inger, Pite, and many others. All of it really surpassed my expectations. I was given the opportunity to collaborate directly on creating new choreographies. That way, I could understand new choreographic methods, and I received all the relevant information first-hand. It was extraordinarily interesting. I was able to explore my potential both as an artist and an individual. Thanks to these collaborations, I acquired a new strength and confidence to be myself and to continue doing what I loved doing – dance.

Working at the NDT does not only mean having a career in performing. For you, it also became a springboard to a career in choreography. Did you always know you wanted to be a choreographer?

To be completely frank, I didn't. But already in school, I sometimes changed my training and choreography routines, and later started designing my own. My desire to create choreographies was gradually growing stronger, but it grew during my time with the NDT, when I started designing choreographies for the NDT workshop. I would finish one, and already I was excited to start working on another. Gradually, more and more opportunities to do choreography arose, until eventually, I decided to leave the company and use the opportunity to create my own works.

Do you think choreography can be learnt, or does one have to be a born choreographer?

A lot of things can be learnt, but the absolute essentials, such as musicality and a sense of space and timing, those you should be born with. That's the way I see it, anyway. Before I personally transitioned into choreography, I'd had a rich and rewarding career as a dancer, which helped me a lot. I got to know many performers, choreographers, and artists. A person always has to be willing to learn.

Do you think that young emerging choreographers have enough space to pursue their own artistic ambitions, or is it necessary to have a “mentor”?

I think it really depends on the individual and how well they can communicate their artistic ambitions. It's important that they do it with passion and sincerity. A mentor can only help you to a certain point. If you can't do the work properly and sincerely, no mentor will ever be able to help you. Ultimately, we're all the architects of our fortunes.

To what degree did Jiří Kylián influence your choreographic direction? Are you not afraid that after so many years of working with him, you will start copying his style?

I really admire Jiří Kylián. He always tried to expand our horizons. He would send us to go see exhibitions and shows and taught us to be more perceptive to our environment. I was really touched by his humanity. He's an incredibly unprejudiced person, and he treats people with complete openness. He picks what he wants from them, and if he sees that it's going somewhere, he supports them. He's always willing to communicate. I really cherish that approach and I view it as a gift. I don't think that I'll ever start copying him. His values and the way he works have helped me be myself, and that's what drives my own growth as a choreographer.

Have you already developed your signature movement repertoire?

I can hardly be judge of that, but I do try to express what I do in an original way.

What's the first thing you do when designing a new ballet? Do you first come up with the idea, the music, or the steps?

That's always different. Sometimes, I come up with the idea first and then look for the right music and everything else. At other times, it's the other way around – the music tells me exactly what I should be doing. I am open and always trying to look for new ways of conveying what I feel.

Where do you look for inspiration?

Inspiration is all around us. I should say at this point that, since 2004, I have worked on most of my choreographies with designer Peter Biľak. Together, we look for new concepts and ways of presenting dance on stage, in film, or even in print. He was the one to introduce me to the visual arts and that has been extremely rewarding and inspiring for me. We always have a lot to think about, and we're always looking for ways of bridging different disciplines and finding the right balance between them.

Masculine/Feminine is a humorous dance miniature. It can be quite difficult to make a dance performance funny. Indeed, such efforts often end in failure. How did you manage to avoid that?

It isn't easy to make a humorous dance show because we don't all laugh at the same jokes. But we tried to explore a theme which is common to our everyday lives, and which is often the subject of different works of art. Masculine/Feminine was my third choreography for the NDT 2 – by then I had come to know the company and the performers pretty well. Gerald Tibbs (director of the NDT 2) gave me carte blanche, and seeing as it wasn’t my first choreography for the company, I decided to go a different way and it paid off. We approached the work in a playful way, and I'm happy that we managed to strike the right balance.

This ballet was initially designed for the NDT. You have now staged it in Brno. Is it easier to create a new show, which you can tailor to the dancers' abilities, or to study a complete choreography with a given company?

When I study a complete choreography with a company, I usually have the opportunity to get to know the dancers better. Afterwards it's easier to create something original for that company. It's a process of exploration and discovery.

Eight characters, trite clichés, the eternal struggle of the sexes... Is Masculine/Feminine based on your own personal experience and observation, or is it pure fiction?

A bit of both, I think. We drew a lot on the book Men are from Mars and Women are from Venus by American author John Grey. Peter Biľak wrote the texts, which were then recorded by professional actors. Staging the show was a challenge like any other. We had to find the right way to translate the content into the movement repertoire. The dancers were very open-minded. When it comes to the creative process, it's very important to work with people who aren't afraid to take risks. We learn from each other.

Set design is a crucial aspect of your shows, and in most cases, it is made by Peter Biľak.

As I have said already, Peter and I work together on most of my choreographies. He and his family live in The Hague, like me. We met by accident at an exhibition when I was still working at the NDT. I began to invite him to my shows, and he introduced me to the world of typography, as well as the world of design and the visual arts in general. When we work on a new project, Peter is always present at the beginning and at the end. In the interim, he serves as more of an external observer who views dance in a different way than I do, which is extremely important. We always have new ideas which we're gradually developing.

Lately you have been dabbling in the audio-visual arts, namely in film. You have even studied at the New York Film Academy, and you have made several dance films. Why did you choose film, of all art forms?

I've always been interested in film. While I was still at the NDT, I would spend my evenings editing short films. I find it's quite similar to choreography. The way you edit a film gives it a certain dynamic. There are infinite possibilities with film editing, as there are with choreography. The human body is very complex and can do a great variety of things, and the things it can't do can be substituted by film. That fascinated me and I began to look for new ways of expressing certain emotions and movements through that medium. Two years after leaving the NDT, I took an intensive course at the New York Film Academy. That opened up new a whole new world of possibility for me. At that time, I was working with Dutch director Ruben van Leer. Together, we made several short dance films which won awards at various international festivals of dance cinema.

Your last work is the film Symmetry, which you shot at CERN. How did you view the environment of the underground scientific complex, where most mortals never set foot? And why did you select that, of all locations?

Symmetry is an ambitious project which we made in collaboration with a really great team. Together with Ruben van Leer and sopranist Claron McFadden, we connected science, dance and opera into a single, half-hour film. Along with that, we also made a half-hour documentary directed by Juliette Stevens. We were filming at CERN and in Bolivia. The environment was chosen based on the script, and because I was playing a scientist, CERN was something of a natural location. We were extremely lucky because at the time, the Large Hadron Collider was out of commission on account of modernisation works. It's a truly incredible place. I often found myself thinking how people could have built something like it a hundred metres beneath the ground. It was immensely inspiring. I only came to really appreciate that some time later, when I was watching the material we had filmed. It was unbelievable.

Do you think that art and science can walk hand-in-hand?

That's a very current question. For some time now, scientific institutions, such as CERN, have been offering numerous forms of interdisciplinary collaboration. They've been trying to open themselves up to the public, so as to seem less remote. I believe that dance and art have a lot in common with science. Of course, scientists work within a completely different framework, they follow very different methods and facts, but in essence, we are all asking questions, and we're all looking for answers. Those answers may not be easy to find, but through our film, we tried to show the audience that art and science can, indeed, go hand-in-hand.

What are your next plans, dreams, and challenges?

When it comes to work, I divide my energies between dance, film, and choreography. I have a voracious appetite for learning, seeing new places and meeting new people. Meanwhile, I try to find some time for my family and friends, whom I love dearly.

Lukáš Timulák